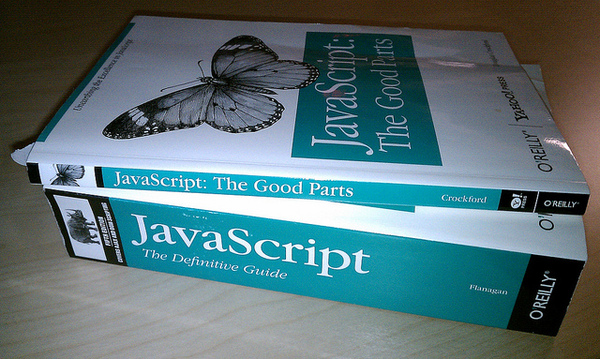

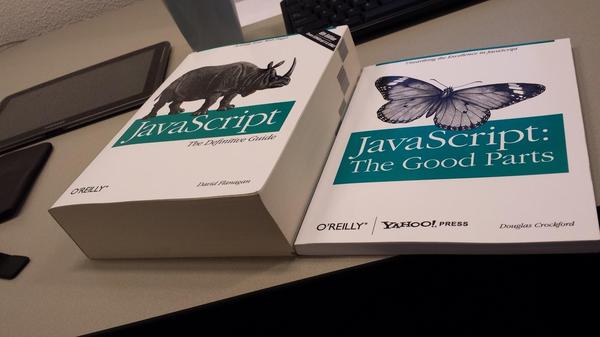

[Part 1]: what if those oreilly memes books were real

Chapter 1: The "It’s Self-Explanatory" Excuse

There’s a special kind of programmer who stares at their screen, watches lines of cryptic code cascade down the terminal, and thinks, “This is art.” To them, every for loop, every if statement, every carefully named variable like data2 or tempFinal_v4 carries a meaning so profound, so intuitive, that explaining it would somehow ruin the mystery.

“It’s self-explanatory,” they declare, waving their hand dismissively when asked why the API returns a 418 error instead of the expected data. “Just read the code.”

The irony, of course, is that “self-explanatory” is the tech equivalent of leaving a cryptic note in a bottle and expecting someone else to decode it decades later. It’s shorthand for “I didn’t feel like writing anything down.” Why waste time on documentation when you can make future developers—or yourself in six months—play a fun little game called “Guess What I Meant”?

But let’s be fair. The “It’s Self-Explanatory” Excuse isn’t born out of laziness. No, it’s a philosophy, a deeply held belief that:

Good code doesn’t need explanations. The fewer comments, the smarter it looks. A clean, undocumented repository is a badge of honor.

Documentation is for the weak. Real programmers debug their way through life. If you need a guide to navigate this jungle of spaghetti logic, maybe you’re just not cut out for this job.

If I can understand it, so can you. Because obviously, everyone else has the same background, thought process, and caffeine intake as the person who wrote the code.

In the spirit of camaraderie, let’s explore a few real-world scenarios where this excuse shines:

Case Study: The One-Liner Genius

In a particularly ambitious moment, Alex wrote a single line of Python code that does something miraculous. When asked about it, they shrug and say, “It’s a one-liner. Just read it.”

result = [x[::-1].capitalize() for x in open("data.txt").readlines() if x.strip()]

What does it do? Who knows. There’s no comment, no README, just this mysterious incantation. Future generations of developers will study this line like ancient hieroglyphics, trying to divine its purpose.

Case Study: The “Modular Mystery”

Sophia’s microservices architecture is a marvel of modern engineering. Every service is perfectly modular, with its own repository, deployment script, and, naturally, zero documentation.

“It’s all self-explanatory,” Sophia assures the team during a meeting. “Service A talks to Service B, which calls Service C. It’s just HTTP requests.”

What she doesn’t mention is that Service B has a hidden dependency on a legacy system written in COBOL, and Service C requires a specific version of Java last seen in 2008.

Why We Love This Excuse

At its core, the “It’s Self-Explanatory” Excuse is an act of faith. It’s a belief in the power of the human mind to decipher anything, given enough time, coffee, and despair. It’s also an unspoken challenge—a gauntlet thrown at the feet of anyone brave enough to ask, “What does this do?”

Because, really, where’s the fun in just knowing what the code is supposed to do?

Pro Tip for Beginners

If you’re new to the art of not documenting your code, here’s a tip: the more confusing your code is, the more confident you should sound when you call it “self-explanatory.” Bonus points if you use phrases like “elegant,” “straightforward,” or “obvious” while describing it.

Remember, documentation is temporary. Confusion is forever.

Chapter 2: “The Code Is Still Changing, So Why Bother?”

If there’s one thing software developers love more than writing code, it’s rewriting it. Codebases evolve at a breakneck pace, morphing from simple scripts into sprawling monstrosities of interconnected logic. And in the chaos of constant change, one excuse reigns supreme: “Why document it now? It’s just going to change tomorrow.”

This excuse is a masterstroke of deflection. It shifts the responsibility of documentation to some mythical point in the future—when the code is “done.” But here’s the kicker: code is never done. It lives, breathes, and grows like an out-of-control houseplant. And as it grows, so does the mountain of undocumented features, hacks, and workarounds.

The Lifecycle of Undocumented Code

Let’s take a look at how this excuse plays out in real life:

Day 1: The Fresh Start The team embarks on a shiny new project. Spirits are high. There’s talk of clean architecture, robust testing, and—dare we say it?—documentation. But someone pipes up:

“Let’s wait until the MVP is ready. No point in documenting things that might change.”Day 30: The MVP Phase The MVP is delivered, but now there’s no time to write documentation because the client has urgent feature requests.

“Let’s wait until the next sprint. We’ll clean everything up and document it then.”Day 365: The Forgotten Jungle The project has gone through 47 sprints, three pivots, and a partial rewrite. No one remembers how the original code worked, and the one person who did has left for another company. Documentation? What documentation?

“It’s too late now. We’d have to rewrite the whole thing just to understand it.”

The Philosophy Behind the Excuse

The genius of “The Code Is Still Changing” excuse lies in its circular logic:

You don’t document the code because it’s changing.

The code keeps changing because no one understands it.

No one understands it because there’s no documentation.

It’s a self-sustaining ecosystem of confusion, and everyone involved learns to embrace it—or suffer.

But let’s not overlook the deeper truths this excuse reveals about the software development process:

Change Is Constant: In the world of agile methodologies, change is celebrated. If the codebase isn’t in flux, are you even innovating?

Documentation Is a Moving Target: Why waste time documenting something that might not even exist in two weeks? Better to wait until things “settle down” (spoiler: they never do).

Future Developers Are Psychic: Surely, the people who inherit this code will intuitively understand its purpose. After all, isn’t that what debugging tools are for?

The Real Consequences

Of course, this excuse has its downsides—minor inconveniences, really. For example:

Onboarding New Developers: “Just dive into the codebase. It’s all pretty straightforward once you figure out the 17 undocumented conventions we’re using.”

Debugging in Production: “This issue only happens on Thursdays when the database server is under load. Oh, and the logic for that feature is spread across five microservices. Good luck!”

Maintaining Legacy Systems: “We wrote this code five years ago when we were experimenting with functional programming. No, we didn’t document it. Why do you ask?”

A Case Study in Futility

Meet Kevin. Kevin is a junior developer who just joined the team. His first task is to fix a bug in a core feature of the application. Armed with enthusiasm and Google searches, Kevin dives in.

The code is a labyrinth of nested functions, magic numbers, and cryptic variable names like x and z1. There are no comments, no README, and no design docs. When Kevin asks for help, the team responds with a shrug:

“That part of the code is still changing. Just figure it out.”

Three weeks later, Kevin has rewritten the entire feature from scratch. It works perfectly, but he doesn’t document it. Why?

“The code is still changing. Why bother?”

And so the cycle continues.

Breaking the Cycle

The “Code Is Still Changing” excuse thrives on a lack of accountability. To break free, teams need to embrace a radical idea: documentation doesn’t have to be perfect to be useful.

Here are some practical tips for documenting code in flux:

Write as You Go: Document the “why” behind decisions, even if the “what” might change.

Keep It Lightweight: Focus on high-level overviews and key concepts. Save the nitty-gritty details for later.

Use Tools: Markdown files, wikis, or even comments in the code can make a world of difference.

Remember, imperfect documentation is better than none. A half-finished map is still more useful than wandering blindly in the dark.

Pro Tip for Masters of Excuses

If you’re truly committed to this excuse, here’s how to sell it:

Use buzzwords like “iterative,” “agile,” and “dynamic” to explain why documentation is unnecessary.

Suggest that writing documentation would slow down progress, even though the lack of it is causing endless delays.

Point out that no one else is documenting their code either, so why should you?

Done correctly, you’ll buy yourself at least six more months of blissful chaos.

Stay tuned for Chapter 3: Chapter 3: “It’s Too Obvious to Write Down.”

![[Part 1]: what if those oreilly memes books were real Мемы, Oreilly, Длиннопост](https://cs15.pikabu.ru/post_img/2025/01/11/11/1736624518184923531.jpg)